A brief overview

COVID-19 has debilitated businesses, international economies and in-person learning experiences, greatly curbing typical human activity and interactions. Though it has taken tolls on several areas of life, some environmental factors—namely various types of pollution—have seen the silver linings of extended stay-at-home periods. Not all categories of pollution have promising futures ahead of them, but let’s dive into what noise, water, light and air pollution are and explore how they have fared throughout the pandemic.

What is noise pollution?

Noise pollution is any noise produced that affects the well-being of humans and wildlife. Noise pollution includes traffic noise, rock concerts, loud inescapable sounds, noise from ships, and can arise from many other sources as well. For humans, noise pollution can cause hearing loss, stress, and high blood pressure. In ocean life, it can affect dolphins that use echolocation (using sound waves to detect objects) to survive. Noise pollution disrupts what and how organisms hear, it interrupts peaceful marine environments, and it poses a serious threat to birds as well.

As stated, noise pollution can have significant effects on birds. In general, some bird species are sensitive to noise, and when under stress due to loud sounds, their behaviors can be altered. A case in point is bluebird reproduction: according to National Geographic, bluebirds have fewer chicks due to noise pollution. Birds tend to fly away when in frightening situations induced by noise, thus waste energy they could have used to find food or rest instead. In addition, since major cities have notable traffic, the urban noise interferes with bird communication, so birds have to emit louder and higher frequency sounds. When loud sounds intervene between birds, flocks or migrations can be affected, as birds use sounds to stay together.

What can be done to reduce noise pollution during the pandemic?

While noise pollution is not a physical danger, it is an invisible danger that can cause health problems to organisms. During COVID-19, in order to stay safe and healthy, it’s ideal to stay indoors and reduce the amount of people outside. This will reduce the transmission of the coronavirus, and as well reduce noise pollution for wildlife, as less cars will be driven and less noise will be produced in turn.

What is water pollution?

There are many different types of water pollution, from plastic/microplastic pollution and the concentration of other debris to chemical pollution, bacterial pollution, and ocean acidification. The main way that water becomes polluted is when humans dispose of waste (physical or chemical) improperly that then makes its way into rivers, lakes, and oceans. This type of pollution is called nonpoint source pollution, when runoff and other pollutants flow to a water source from many different places. Aside from the collection of plastic and other toxic debris, the main type of nonpoint source pollution that we have to worry about in our oceans is chemical runoff from agricultural sites and waste processing plants. As non-organic farmers irrigate their fields, the excess water mixes with the pesticides and eventually makes its way to streams, then rivers, then finally the ocean, where all the toxic chemicals picked up along the way accumulate and harm wildlife. The same can be said for many waste processing plants, sewers that produce runoff, and damaged septic tanks, except instead of introducing chemicals into oceanic ecosystems, they introduce multitudes of harmful bacteria into the water. These types of pollution in freshwater and saltwater contribute to low water quality, which is measured by bacteria levels, particulate levels, chemical levels, salinity, and the amount of dissolved oxygen present.

Locally, water pollution remains a concern, but things have been looking up lately. A July article published in the Marin Independent Journal reports that the water quality at some of Marin County’s beaches was measured for 2019-20 using the same criteria. The organization that conducted the study, Heal the Bay, gave 24 of the beaches surveyed “outstanding marks” for the low levels of E. coli and enterococcus bacteria in the water. The only beach that didn’t receive an A grade was Stinson Beach, which received a grade of F. However, this was attributed to the storm that had occurred a few days before testing, washing a large buildup of contaminants from the land to the sea. The beach was later re-tested and received an A grade that matched Marin’s other beaches.

How has water pollution fared during COVID-19?

Combined with the low levels of rainfall seen this year, shelter-in-place orders that were put in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 have had positive effects on water pollution. Whether these impacts will be short or long-lived is unclear, but for the time being, the pandemic has brought about visibly positive environmental shifts. In Venice, Italy, the canals that crisscross the city have become clearer than ever, and marine life has been seen swimming there for the first time in years. This narrative has played out in many other places around the world, albeit not as extremely. For example, in a study of Vembanad Lake in India, it was found that since the start of the quarantine there, the suspended particulate matter (silt, rocks, plastic debris) in the lake was down 15.9% compared to normal levels.

The drop in contaminants seen in lakes and oceans across the world from the pandemic is largely due to the lowered demand for imported goods and the lower level of boat activity by tourists. According to the United Nations Development Program, tourism, fisheries, offshore oil and gas production and shipping have been the most affected industries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the amount of cargo being shipped internationally has declined 5%, and container shipping has declined 10% in 2020, the largest decrease on record. Being some of the higher contributors to ocean pollution, their lowered output has had a beneficial impact on water quality for the moment.

Once restrictions around the pandemic ease and water vehicle traffic increases again, it is likely that contaminant levels in our oceans and lakes will rise again to normal levels. For now, we can only hope that the beneficial impact that pandemic restrictions have had on the hydrosphere has shown us what just a few short months of using less fossil fuels can do for our water.

What is light pollution?

An endangering byproduct of industrialization, light pollution finds root in several sources and can have numerous adverse effects on wildlife and human populations. Primarily, this type of pollution originates from excessive artificial light let off by outdoor sources such as streetlamps, automobiles, stadiums, properties and large advertisements. Though this illumination serves to guide people throughout the night, light pollution has greatly smudged our view of the galaxy; the phenomenon of “sky glow,” where human-produced artificial light fades celestial objects from our vision, is a disquieting factor for many astronomers. Urban areas with high concentrations of artificial light bear the brunt of sky glow, but according to National Geographic, 99 percent of Europeans and Americans live in areas affected by it.

Many sources of outdoor light are inaptly placed, and thus spill light into unwarranted and unnecessary areas, which can take a toll on those nearby. Dubbed “light trespass,” this type of light pollution can make for sleepless nights or may prompt feelings of encroachment amongst close neighbors. Another variety of light pollution is “glare,” which is excessive light that strains the eyes of surrounding beings. “Clutter” falls under a similar, yet separate category, where bright light is tightly packed in configurations that may distract bypassers. Regardless of the type of light pollution, the surplus of artificial, nocturnal light can be detrimental to natural bodily functions and processes in wildlife and people. Predominantly, it can interfere with one’s circadian rhythm and the production of melatonin, a hormone that can generate a plethora of issues including stress, fatigue and headaches if offset.

Though light pollution can impede on sleep health and some other aspects of human life, it influences animal life on several grave scales. Some migratory species like birds and sea turtles that follow the moon while relocating can be misdirected and fall off course. Insects that are inherently attracted to light often perish when making contact with hot, artificial sources of it. In turn, countless species that rely on insects for nourishment face declining availability, which can have unfortunate repercussions on food webs. For amphibians that croak nocturnally as a breeding practice, light pollution can throw off perceptions of time and consequently decrease repopulation efforts. Some carnivorous mammals have employed light pollution to their advantage, turning artificially illuminated areas into hunting grounds that naturally attract some species. Conversely, other mammals typically marked as prey by these carnivores—like mice—have outsmarted these new tactics by eating in darker regions, which also takes a toll on natural interactions within food webs. Because these and many more populations have been impacted in countless manners, light pollution remains a cause for concern.

How has COVID-19 impacted light pollution?

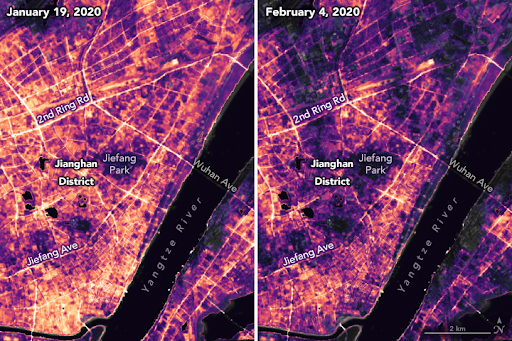

Since nationwide lockdowns and stay-at-home orders were issued in mid-March, light pollution has fared well—several populations have observed declines in its presence. While it was much less present around the beginning of mandated quarantines, as many sources worldwide claimed to have clearer views of starry night skies, it still remains lower than normal. Largely due to the standstill of transportation, urban activity and nightlife, the relative decrease in light pollution has been observed and appreciated by many—some have even gone stargazing.

What is air pollution?

Air pollution is mostly due to emissions from motor vehicles and factories. It has become one of the most pressing environmental problems concerning global warming. Air pollutants such as greenhouse gasses are mainly responsible for the destruction of the ozone layer, which protects us from harmful UV rays. The effects of air pollutants can mainly be seen in cities where the concentration of vehicles is much higher than average such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Beijing. In cities such as these, it is not uncommon to see a cloud of dark smog polluting the ocean views making the city air hard to breathe for humans and animals alike. In Mexico City in 1986, the air pollution was so intense that people reported “birds falling from the sky.” In Beijing in 2013, the smoke from nearby wildfires was so consuming that when people returned, they reported seeing multitudes of birds killed from smoke inhalation.

But what exactly is in smog and smoke that classify them as air pollutants? Smog is dense, dirty air that contains carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, ozone, and other particulate matter that is toxic when inhaled. Smoke on the other hand, results from the burning of organic materials, and is essentially natural (although sometimes toxic) gas mixed with particles of carbon. Along with toxic gasses, the particulate matter less than 2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5) in smog and smoke is what can get inside the respiratory system and cause so much damage to both birds and humans. It is believed that birds are actually more affected by air pollution than humans due to the fact that they have higher respiratory rates, but the symptoms of pollutant inhalation are much the same. When there is long term exposure to nitrogen oxides and ozone, inflammation of the esophagus, blood vessels, and bronchi can occur leading to lung failure. They can also result in hemorrhaging, necrosis of epithelial capillary cells in the lungs, and pulmonary edema: a symptom of pneumonia. These symptoms are found in birds as well, but other emissions from vehicles called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have been shown to result in reduced growth, increased abandonment of nests, lower egg laying and hatching rates and lower red blood cell counts. Specifically in a study done on Double Crested Cormorants, it was found that exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and PM2.5s resulted in permanent DNA mutations that could be passed down to offspring.

How has COVID-19 affected air pollution?

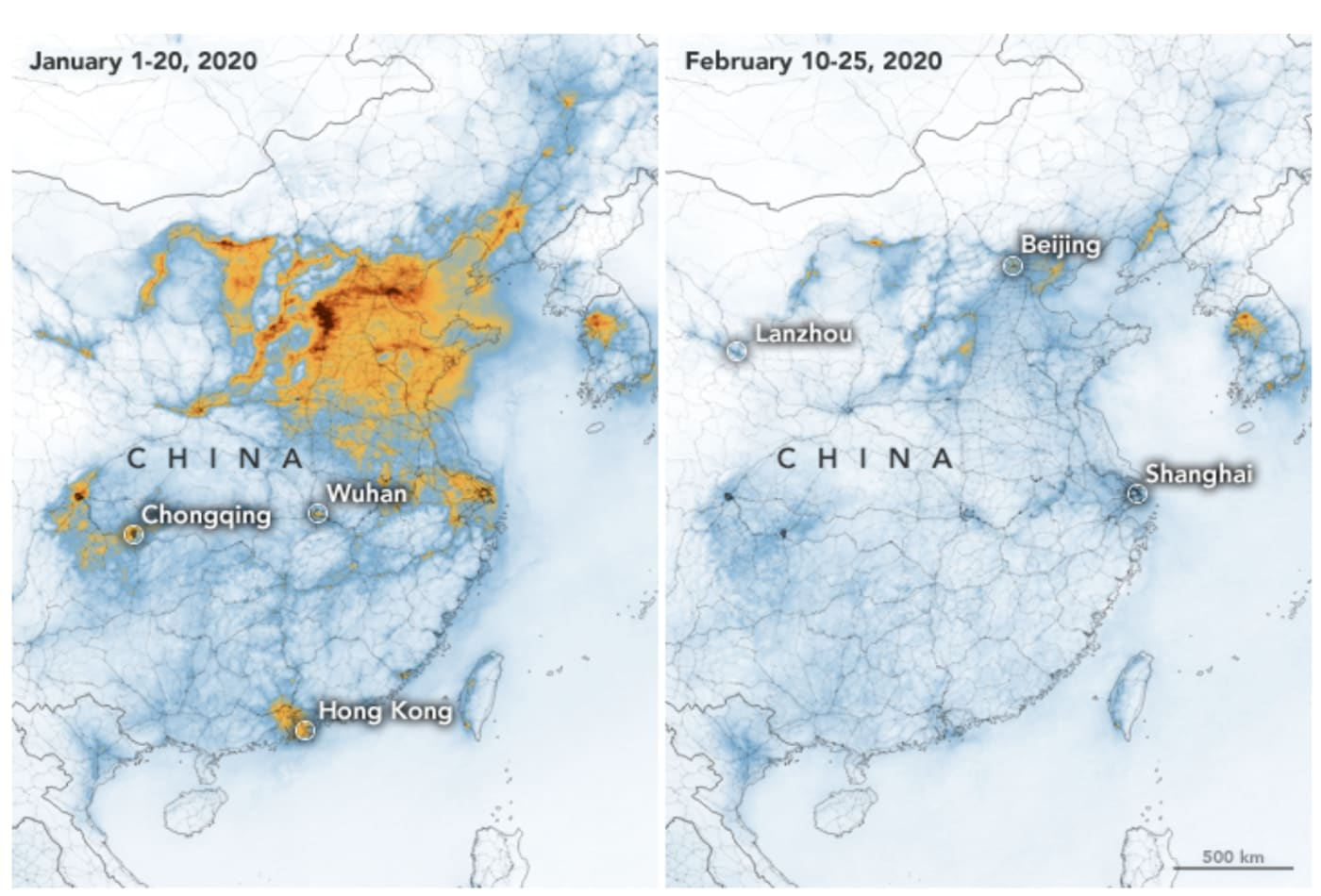

There is a little hope in the story of air pollution. During the COVID-19 pandemic that has devastated the globe, the reduction of the use of motor vehicles due to the lockdown orders has resulted in major improvements in air quality in many cities. According to data published by the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute using the satellite Copernicus Sentinel 5P, nitrogen dioxide and PM2.5 levels above Paris have dropped 54%, and have dropped almost 50% in cities like Milan, Madrid, and Rome. In China, the concentration of the harmful PM2.5s has dropped 35% while their carbon dioxide emissions are down almost 50%. Cities around the world have seen clear skies for the first time in many years due to the sudden drop in emissions during the COVID-19 lockdowns, and while the progress in air pollution might not be permanent, the birds have returned.

So, what can we draw from this?

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in shelter-in-place orders in many places around the world. Although the spread of the disease is rampant, especially in major cities, there have been numerous positive effects on environmental problems such as air, light, water, and noise pollution due to the lower usage of motor vehicles and general deceleration of typical human activity. These improvements have allowed some species of animals to return to more urban areas, including—but not limited to—deer, fish, and birds. These shifts may be temporary due to the ever-evolving status of lockdowns, but hopefully they provide us the insight needed to fight for environmental protection, as they demonstrate how heavily birds and other animals are affected by human-generated pollution.

Resources not hyperlinked:

-

Houston, W. (2020, July 12). Marin County beaches receive 'outstanding' water quality ratings. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.marinij.com/2020/07/11/marin-county-beaches-receive-outstanding-water-quality-ratings/

-

Yunus, A., Masago, Y., & Hijioka, Y. (2020, April 27). COVID-19 and surface water quality: Improved lake water quality during the lockdown. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969720325298

-

Sanctuary, F. (2011, April 07). Water quality describes the condition of the water, including chemical, physical, and biological characteristics, usually with respect to its suitability for a particular purpose such as drinking or swimming. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://floridakeys.noaa.gov/ocean/waterquality.html

-

Hudson, A., & Replication-Receiver. (2020, June 08). The ocean and COVID-19. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2020/the-ocean-and-covid-19.html

-

McMahon, J. (2020, April 17). New Data Show Air Pollution Drop Around 50 Percent In Some Cities During Coronavirus Lockdown. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffmcmahon/2020/04/16/air-pollution-drop-surpasses-50-percent-in-some-cities-during-coronavirus-lockdown/

-

Gohd, C. (2020, May 13). Air pollution levels will bounce back as COVID-19 restrictions loosen, scientists say. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.space.com/air-pollution-increase-covid-19-coronavirus.html

-

Bowler, J. (n.d.). New Evidence Shows How COVID-19 Has Affected Global Air Pollution. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.sciencealert.com/here-s-what-covid-19-is-doing-to-our-pollution-levels

-

Earth Matters - How the Coronavirus Is (and Is Not) Affecting the Environment. (n.d.). Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/blogs/earthmatters/2020/03/05/how-the-coronavirus-is-and-is-not-affecting-the-environment/

-

Qin, K. (2016, March 03). Birds suffer from air pollution, just like we do. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://ca.audubon.org/news/birds-suffer-air-pollution-just-we-do

-

Sanderfoot, O., & Holloway, T. (n.d.). Air pollution impacts on avian species via inhalation exposure and associated outcomes. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8051/meta