Everywhere we look in our lives today, we’re reminded of our contributions to climate change: the smoking tailpipe of a passing car, leaving a light on when we leave a room, and even turning on the stove are all indications of the largely invisible ways we contribute to a warming world. But how does this really hurt our atmosphere, and how badly? Scientists have been warning of reaching a tipping point into disaster for years, and yet we’re still here, driving our cars, using electricity, and cooking our food. Is the climate “crisis” not as bad as scientists claim?

The truth is, our atmosphere is fragile and we are running headfirst towards a point of no return, which, once passed, will have catastrophic consequences for the health of the world and everything that inhabits it. The start to repairing our world is educating one another on this issue that faces all of us today: air pollution.

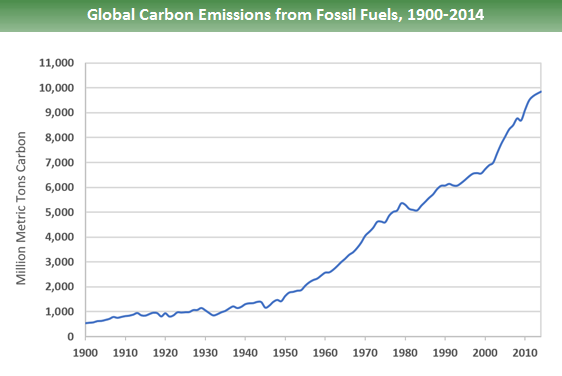

When most people think of air pollution, their mind immediately goes to carbon dioxide. In recent years, even with increased education and awareness of global warming, carbon emissions have only gone up. Indeed, CO2 is one of the most prevalent greenhouse gases in the story of climate change. However, many man-made chemicals we interact with daily are thousands of times more warming than CO2.

Some harmful chemicals actually cool our atmosphere, even as they choke out cities and harm human lives by exacerbating health issues among sensitive groups. We all know driving gas-powered cars and lighting fires can release climate-warming gases, but did you know that running your refrigerator and air conditioning can be just as detrimental? For humans to combat our climate crisis and preserve our natural world, everyone needs to become educated on how to preserve our atmosphere, and that starts with understanding how we harm it on a daily basis.

For years scientists have told us our planet is warming because of carbon dioxide, but how? What makes this gas different from the others naturally and artificially present in our atmosphere? The truth is, CO2 isn’t unique at all in its ability to warm our planet — many gases share this same property. When infrared radiation from the sun reaches Earth, it hits the surface, warming it slightly before bouncing off into space. Greenhouse gases absorb some of these wavelengths before they exit our atmosphere, then re-emit the radiation, heating our planet even further. Thus 1 unit of sunlight gives us 2 or more units of heat depending on how many times it’s absorbed.

Though carbon dioxide is the most anthropogenically emitted greenhouse gas, it’s also one of the most mild in its warming potential. Developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, scientists use a scale to measure a chemical’s global warming potential by comparing one kilogram of the chemical to one kilogram of carbon dioxide. Common gases like methane and nitrogen can have a few times the warming potential, while other gases like refrigerants can have 10,000 times the impact per kilogram.

All of these gases add up fast, quickly reaching dizzying totals. According to the EPA, 13.2 trillion pounds of carbon equivalent greenhouse gases were released in the year 2020. But 13.2 trillion pounds means nothing to the average person until put to scale. All of the water in our oceans weighs 13.6 trillion pounds. All of the copper on earth weighs 13.2 trillion pounds. All of the sand in the Sahara Desert weighs 13 trillion pounds. Even with these metrics, it is still a daunting task to understand the obscene amount of warming gases we release annually.

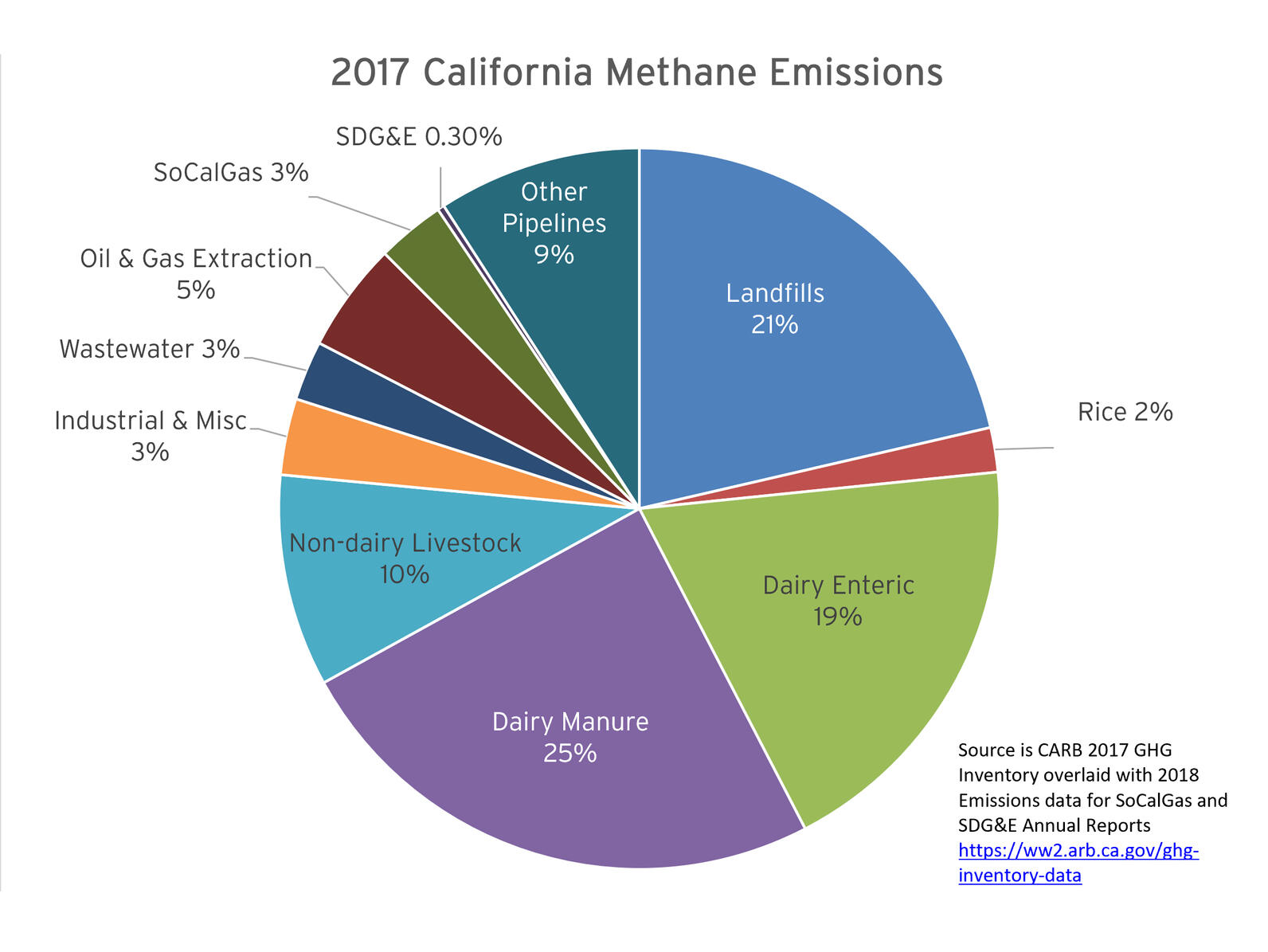

With carbon dioxide taking the global stage as a common enemy, many other greenhouse gases continue to be overlooked by the public eye. Methane especially is a huge climate warmer, with a warming index of 25 times that of CO2. Livestock production is the largest contributor of methane, specifically cows, releasing 100 kilograms of methane for every 1 kilogram of beef.

Many methane-producing industries have begun burning their byproduct for heat and energy with a process called biogas cleaning, also allowing it to break down into CO2, which is a less harmful compound. By investing in technologies like this, everyone wins: energy prices go down, as well as carbon emissions, while farms and other methane producers gain extra profit as an incentive. Solutions like this are essential for saving our climate in a world full of conflicting interests.

Some atmospheric pollutants have a more ambiguous effect on climate and health than their warming greenhouse gas counterparts. Ozone, for example, is a pollutant near ground level but forms a critical atmospheric layer higher in the stratosphere.

As harmful UV rays from the sun enter our atmosphere, our first line of defense is the ozone layer. Ozone’s chemical formula is O3, meaning 3 oxygen atoms are bound together. The energy of the UV rays is absorbed and splits the ozone into O2 — or atmospheric oxygen —and a single, unstable oxygen atom, which quickly rebinds itself to the O2 to make a new ozone molecule. Thus, harmful radiation is quickly dissipated, keeping our skin and eyes safe from dozens of miles above the earth’s surface.

However, certain ozone-depleting chemicals can bind with the single oxygen atom in our stratosphere, preventing it from reforming ozone. This thinning allows more UV energy to enter our stratosphere and increases the risk of eye and skin damage, including various cancers.

The largest contributors to this problem are chlorofluorocarbons, also known as CFCs. CFCs are gases found in refrigerants and aerosols. When CFCs enter the atmosphere, the chlorine atom present in them bonds with the single oxygen as described above. Not only do they deplete our ozone, but CFCs also have several thousand times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. Luckily, CFCs were phased out nearly worldwide in 1989 after an international climate summit in 1987 known as the Montreal Protocol. However, these chemicals are extremely persistent and long-lasting, so even after 36 years of them not being produced en masse, they still deplete our ozone.

Stagnating the production of CFCs was not without its drawbacks. They were replaced by HFCs, or hydrofluorocarbons, which break down in our atmosphere much quicker and therefore are less harmful to the ozone layer. The solution is imperfect, however, because they also have a staggering global warming potential of 14,800 times that of CO2. By helping to solve our issue of ozone depletion, the technology used had the drawback of contributing to another issue: global warming.

One of the leading possible solutions to our issue with refrigerants is an unexpected contender, a gas normally used to heat instead of to cool: propane. Propane exhibits similar refrigerant properties to CFCs and HFCs, all while not affecting our ozone layer and also not being considered a greenhouse gas. Not only this, but propane is actually cheaper than traditional refrigerants. Propane is already widely used as a refrigerant in certain parts of the world such as China; however, due to flammability regulations, it has not yet been utilized in the U.S..

Lifestyle choices like cutting down on meat consumption and air conditioning use paired with the development of technologies such as propane refrigeration and biogas cleaning are essential to the survival of our planet. However, even excellent solutions like this, with limited drawbacks but that require possible investment for research and development or personal sacrifice, are often overlooked. At its core, climate change is simply “too large and scary an idea to understand, and people use denial as a defense mechanism,” according to an article written by Maya Kattler-Gold, a researcher with the Seaside Sustainability non-profit organization.

In other words, fathoming the idea of a dying planet is too much to handle, and rightfully so. Our generation may not have started this issue, but that does not mean that it doesn’t affect us, nor is it not our responsibility. As a society, we have an ethical responsibility to our future generations to leave our planet better than how we found it, and that starts with reducing our impact on our atmosphere.