Our current global system, both economically and geopolitically, is designed to contribute to carbon output which changes climate in a negative manner. The way that the global economy is structured relies on inherently anti-environmental practices. While there is a significant cultural movement in the right direction to mitigate the damage to the environment, the changes are attempting to operate within a system that will no longer allow humans to progress — in fact, capitalism will only rush us toward a future that is not viable.

We need to act urgently, and with each generation that passes, the problem of environmental degradation becomes more pressing. Within your lifetime, you have probably already noticed the effects of climate change, and those are only going to increase in intensity if we don’t make a fundamental global change. Our current world isn’t set up to be able to make that change; the economy focuses on globalized businesses and corporations instead of on the survival of our — and other — species.

There are many factors in the systematically unsafe practices performed by companies and allowed by governments all over the world: whether it’s the economic sectors themselves, supply chains, lack of subsidization, or the control of giant harmful corporations, the evidence of capitalism’s harmful influence on natural resource use is not hard to find.

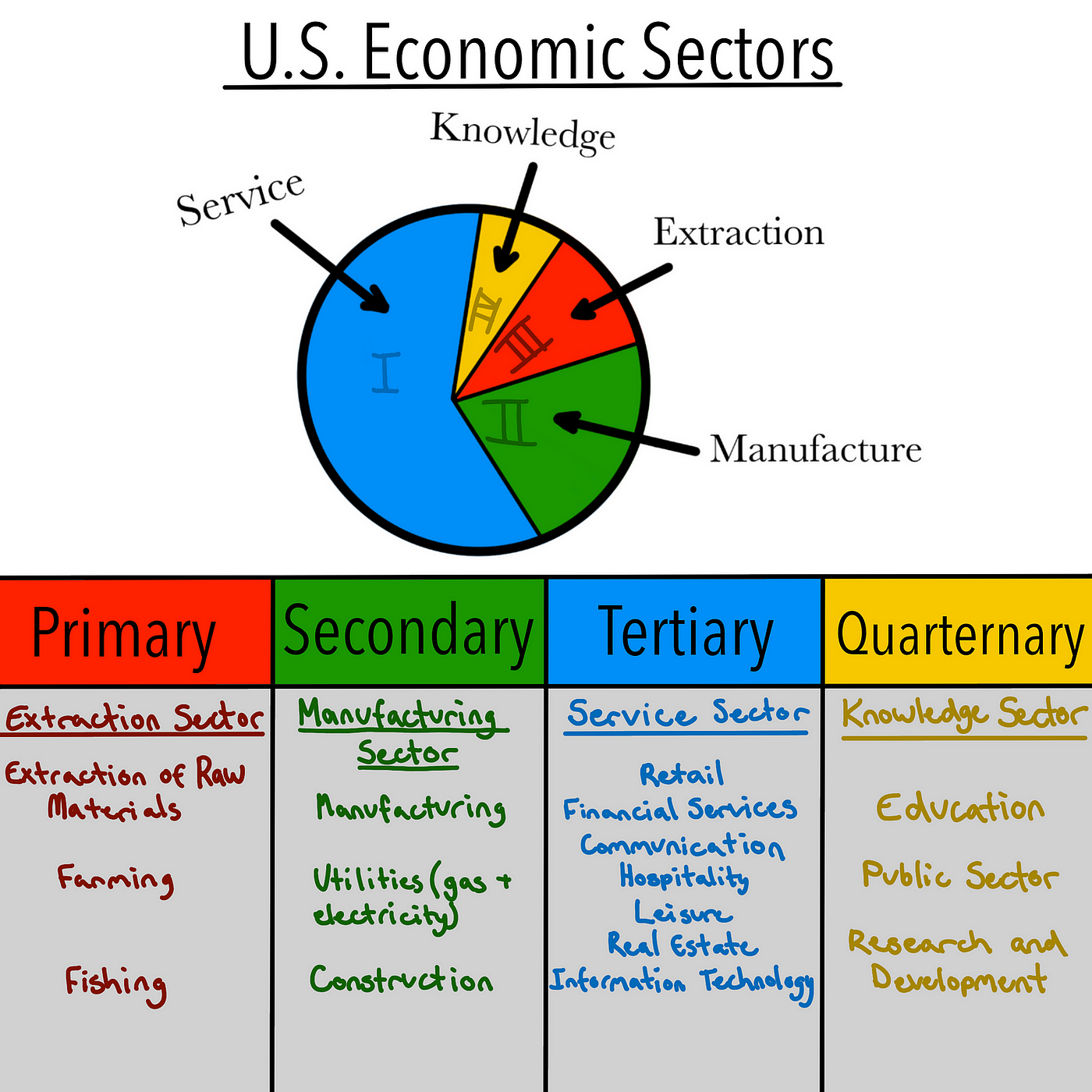

To understand why the issue is central to the global economy, it is important to first understand economic sectors and how unhealthy practices benefit that economy.

The 4 basic sectors of the economy are Extraction, Manufacturing, Services, and Knowledge. Each sector handles a different part of society. In past decades, first-world countries have adjusted the ratio of these four sectors and skewed their relative economies into the service sector. The U.S. is a perfect example of this.

Shifting towards the service sector led to the outsourcing of labor, particularly in manufacturing, to countries where the cost of living — and labor — is cheaper. The outsourcing of labor had many unintentional consequences such as fragmentation of the supply chain, destroying company loyalty, and eliminating blue-collar jobs from the domestic workforce. This cycle perpetuates itself, shifting businesses into globalized companies or corporations.

Our worldwide economy functions, in part, as a result of global corporations whose reach spans multiple continents. With this expansion comes the need for supply chains, the process through which a company turns raw materials into finished goods and services.

I spoke with Lucas Oshun, Director of Regeneration Field Institute (RFI), proprietor of Los Arboleros Farm in Coastal Ecuador and supply chain consultant in wood and bamboo products for Global Bamboo Technologies and BamCore Inc., about the reality of our supply chains. We discussed the systemic issue at play in our global economy where both supply chains and the extractive sector of the economy are largely negatively impacted by the system.

Supply chains are a core part of our global infrastructure but are rarely eco-friendly. Oshun has been working in the environmental field for about 14 years. “When it comes time to, ‘Where do you cut costs?’, and then with far off places where wood or bamboo are grown, they are out of sight and out of mind so they can quickly become just numbers on a spreadsheet,” Oshun says. “With those numbers and driving them down, they have real-world ecological and social consequences.”

If there was a global push for subsidies and environmental action that wasn’t localized, it is very possible for there to be such thing as an eco-friendly supply chain. There is a lack of global recognition and effort in enforcing government action on behalf of the environment. “There is not enough recognition of the historical dynamic, for example, between the United States and the global South: exploitative, extractive, practices and supply chains that create environmental consequences and social and political consequences. And, we don’t have a foreign policy or much in the way of resource allocation to remedy what we contributed to cause in the first place and just say, that’s for the private sector to figure out,” says Oshun.

Oshun also mentions that the lack of support from governmental subsidies affects companies trying to do the right thing, and even individual farmers have less incentive to produce sustainably, in part, because there is no economic support for them to do so. It is much easier to continue causing damage than to take the leap and sacrifice to help heal it. “Those companies are trying to be sustainable and they’re trying to create competitive construction materials made out of bamboo. Even the fact that they are doing that means that they have strong values and motivation towards sustainability, but they should be getting more support because the public sector supports a lot of things that contribute to environmental degradation and so does the private sector," Oshun asserts. "If there is a company that is aiming to create a carbon neutral, carbon negative, or high social-environmental benefit supply chain, people should throw resources behind that because a lot of the reason that they have those resources in the first place is because of those environmentally exploitative practices in their other supply chains or other business activities.”

The globalization of companies in the 1990s and 2000s has created a system that needs to be changed on a global scale. Domestic subsidies help each individual country but don’t attack the root of the problem because these shifts need to happen on an international scale.

Instead, government support currently goes to massive corporations whose ambitions largely prioritize the bottom line and not the future of human society. A good example of this would be the plastic industry and the lie that is the recycling process.

A few years ago, a study discovered that many plastics companies were also fossil fuel giants who had turned their attention to plastic in light of the decreasing usage of fossil fuels. The transition to plastics was a way for fossil fuel giants to escape criticism for their anti-environmental practices by putting the responsibility of sustainability on the consumer. They are huge global corporations such as ExxonMobil (who last year had revenue of $376.977 billion), Sinopec ($482.68 billion), BP PLC ($254.672 billion), and Chevron($222.806 billion), just to name a few. These companies profit immensely from the destruction of our planet. When the fossil fuel market took a dip, they pivoted to plastics as a way to make money, all whilst selling the consumer on the made-up concept of recycling. According to the UN Environmental Program, only 9% of all plastic ever made has been recycled. (UN Environment Program)

I say made up, not because it doesn’t exist, but because the idea that everything we throw into our blue bins is recyclable is a myth that those companies pushed in order to prevent backlash. In 1989, fossil fuel executives used lobbying to ensure that a recycling symbol would make it onto every piece of plastic, regardless of whether or not it was recyclable.

Why? Because of the way our global economy is set up, it is not economically viable for these companies to commit to our future. Ron Liesemer, an ex-DuPont employee who took over the Council for Solid Waste Solutions, said it best: “Yes, it [recycling] can be done, but who’s going to pay for it? Because it goes into too many applications, it goes into too many structures that just would not be practical to recycle.”

The economy rewards these harmful practices by making the industry over $400 billion dollars a year in plastics alone, and people get punished with a polluted world as a result. According to data from the UN Environment Program, 1,000 rivers are accountable for nearly 80% of global annual riverine plastic emissions into the ocean.

So long as the global economic systems reward harmful practices through financial gain, it will remain impossible to go green. The initiative needs to be taken by governments to support ventures with strong values to economically motivate more companies to operate sustainably. As there is no economic incentive for these companies to do better, there will be no change.

This change, however, is crucial for our survival. As Lucas Oshun said, there is this lack of urgency when it comes to educating and preparing the next generation, or even this generation, to deal with the problematic system we have created and begin to heal our planet for the chance of a future. We need to act now and change the global system from one set up on profiting from the environment to one that works with it collaboratively. By doing a complete overhaul of the global economic rewards system, we stand to further our potential as a species.

The following is the full transcript of an interview with Lucas Oshun.

What is your perspective on how supply chains are set up? Would you consider them to be eco-friendly?

Lucas: I, generally speaking, would not consider most supply chains to be eco-friendly. Typically companies are just out to get the cheapest products possible and they almost exclusively rely on other third-party certifiers like the Forest Stewardship Council, FSC, or you know, in the case of agriculture Organic or Fair Trade Certifications or Rainforest Certifications. They almost exclusively rely on those people to ensure that certain types of social or environmental practices are being adhered to. So most enterprises don’t have the personpower to sort of, vertically integrate and develop their own well-thought-out supply chains. So even when a company might have the value to do things in an ecologically or socially great way, they’re often “not able to” allocate the resources to ensure that and I think, part of that is just the capitalist system that we live in, part of it is not enough support from government to help subsidize making that possible. It’s often the case that not enough resources are spent on that because starting a new company takes tens of millions of dollars and that comes from shareholders. And then there is pressure to provide the greatest or the promised returns to shareholders, which is probably how the people who run the company get the money to begin with, is by convincing them they’ll receive these returns. So when it comes time to where do you cut costs, and then with far-off places where wood or bamboo are grown, they are out of sight and out of mind and so they can quickly become just numbers on a spreadsheet. With those numbers and driving them down, they have real-world ecological and social consequences.

Would you say that if there was more government support and economic incentives, that something like a net zero supply chain would be possible? Or do you think that that’s just not in the cards?

L: No, I think it could be. You know, if you were to take some of the subsidies, give them to the industrial agricultural sector, and begin transitioning, offering the subsidies to farmers or producers to be able to make the transition towards an ecological way of doing things, and it would require a macro-financial analysis to make a sturdy claim about it but I think it’d have real positive impacts. And I think one basic problem is that those efforts are usually focused on domestic stuff. There might be some here, domestic subsidies going to farmers to convert towards less carbon-intensive farming but, supply chains and companies are inherently, at this point, global and so are carbon emissions and so is climate change. There is not enough recognition of the historical dynamic for example, between the United States and the global South: exploitative, extractive, practices and supply chains that create environmental consequences and social and political consequences. And, we don’t have a foreign policy or much in the way of resource allocation to remedy what, maybe, we contributed to cause in the first place and kind of just say, oh, that’s for the private sector to figure out. But the transition is not cheap. On our farm we have really compacted soils, a lot of damage was done over the course of 30–40 years of cattle grazing there so, to not use chemicals, to not use shortcuts that cause more environmental problems in order to get short term yields and returns we need to invest in long-term things that are ultimately costly. And we have a business model with our education program that allows us to make those investments but it’s still hard, and it’s still an economic stress for us to try to do regenerative agriculture. So, imagine a farmer that doesn’t have an alternate source of income, and is just relying on the productivity of their agricultural practices. It’s not particularly viable without support but doing that and achieving those regenerative gains doesn’t just benefit the farmer, it benefits everybody downstream from them literally and figuratively speaking.

How would you say the bamboo supply chain is a reflection of the overall problem within supply chains and the overall economic ties of that?

L: Just that, the only sources of bamboo that are really being considered for the industrial supply chain are from larger scale plantations so the smaller scale producers are left out of the opportunity. Also, there’s a lack of localized value-added processing.

The people with the capacity and technology to do the value-added processing after the harvest of different timber and agricultural crops are typically from developed countries but the people trying to make the start-ups and the companies trying to engineer bamboo products in Europe or the US or Asia, they’re also startups, so they’re vulnerable and have limited resources, so they need the “slam-dunk” supply chain solutions but they don’t have them, so they’re having to create them and that’s expensive to do and disincentivizes some of the cooperative work, bringing together many small producers and just all those things have high logistical operational costs. So, they look to 1 or 2 big producers and then say that it’s bamboo, so it’s green, so it’s good by leaving out some of the more horizontal benefits that could be created by that supply chain and leaving out really optimal sustainable management practices that might be achieved if more emphasis was placed on that and there were more resources available ultimately.

So is there a lack of economic incentive or motivation to be sustainable?

L: Right, or just, support even, is probably a better way of putting it. Those companies are trying to be sustainable and they’re trying to create competitive construction materials made out of bamboo. Even the fact that they are doing that means that they have strong values and motivation towards sustainability but they should be getting more support because the public sector supports a lot of things that contribute to environmental degradation and so does the private sector. If there is a company that is aiming to create a carbon neutral, carbon negative, or high social-environmental benefit supply chain, people should throw resources behind that because a lot of the reason that they have those resources in the first place is because of those environmentally exploitative practices in their other supply chains or other business activities.

[Ecologically friendly farmers] are the ones that are doing the most expensive type of farming, they’re the ones that are doing the right thing, they are the ones that are taking a leap of faith and risks to not use these contaminating ways of doing business and then why on top of all of that are they the ones that a required to pay for their own certification? I thought that was a good point. I never really thought about it like that but it’s true, that’s what we’re doing because we’re doing a more expensive type of farming, we can’t even afford to keep paying for organic certification but why should we have to? We’re the ones who are already going above and beyond to do things in an ecological and socially responsible way

What has been the biggest systematic flaw you have witnessed since being in the environmental sector?

L: Maybe, in the education system. Realistically, a lack of urgency even at the university level. Really double down on preparing the young people with the skills they’ll need for the future. That people could graduate with engineering degrees without at least a couple of classes focused on renewable energy, that’s crazy. That people could graduate with an Agricultural degree without at least several classes focused on transitioning toward sustainable land management, that’s crazy. It can’t just be, you can’t just continue to treat it like it’s this niche, “if you’re into that kind of thing” type of thing, it has to be something that is considered of mainstream urgency. That’s what I would say, I mean certainly in the private sector, in the government, we have to look at the people, the future professionals coming down the pipeline and think about how realistically we are preparing them, or not preparing them, to inherit the future and to create the solutions that we need.